Exploiting Cyclical Companies For Outsized Returns — Part [1/2]

“When business is booming, people convince themselves that the growth will never stop. And when times get tough, suddenly everyone believes the downturn is here to stay.”

I recently invested in one steel products manufacturer that’s currently trading at just 28% of its book value, 62.5% of its NCAV, and less than half of my estimated liquidation value. Profitable every year since 2012.

Most of the assets are tied up in working capital, and debt levels remain minimal. The financial reports don’t show anything even remotely concerning, and with management effectively controlling the company, their incentives are reasonably aligned with shareholders.

Since my last brief writeup, its stock price has dropped by nearly 30%:

(now that I think about it, that probably isn’t the best promotion for that article…)

The main culprit here was continued margin pressure from broader macroeconomic issues in the European steel industry, leading to a net loss of 0.34 PLN per share for the first half of 2024.

It’s mostly macro

The main issue seems to be industry-wide rather than company specific. Steel prices have taken a nosedive since 2023 due to rising production costs squeezing earnings. There’s also less demand across Europe.

On top of that, Chinese steel imports are undercutting local prices, adding to the pressure.

So, it’s mostly macro stuff - nothing too complicated.

Historically, this company’s P/B ratio has ranged from as low as 22% in 2020 to as high as 177% back in early 2012. It wasn’t unusual to see it trade between 60-80% of book, so when things get better, there’s certainly a chance for this stock to double.

Why I love cases like that, and why you should too

What I like about these situations is that there’s nothing inherently wrong with the company itself. It’s just that the macro environment is getting worse, which naturally impacts current earnings and drags the stock price down.

But the industry will, at some point, get better. Earnings will get better.

And that’s all there is to it.

The play here is simple: find a good entry point, start with a small position, add more if it dips further, and let mean reversion work its magic. You see this a lot with cyclical companies - they may often not be of the best quality, sure, but they regularly get extremely undervalued. And when they do, you should exploit that.

Classic cigar-butt investing.

I know it sounds just too simple to work - that’s how the majority thinks as well.

And this, my friend, is key.

First, a success story

This reminds me of a company I used to have a significant position in a few years back - Universal Stainless & Alloy Products (USAP). It was in a very similar spot to the one I want to share with you today.

I first bought USAP at $10.50 per share back in 2021, starting with a small position. Just a few percent of my portfolio, no more than that.

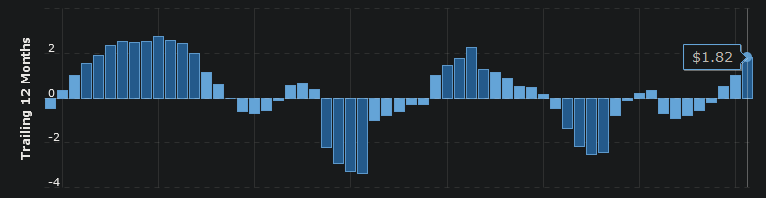

At the time, the stock was trading at around half my fair value estimates. It wasn’t anything special, but it looked cheap quantitatively. If you look at the chart below, you can clearly see the cycles and how market sentiment has swung over the years.

Since 2000, there have been 5 distinct opportunities just waiting to be exploited for an exceptional return.

This company is a perfect example of how cyclical industries work. There are good times, and there are bad times. Ups and downs are just part of the game. But when the extremes happen, the market starts acting like the current environment is the ‘new normal’.

When business is booming, people convince themselves that the growth will never stop. And when times get tough, suddenly everyone believes the downturn is here to stay

Do you see what I’m getting at?

The market tends to forget that in a cyclical industry, the bad times usually don’t last forever, just like the good times don't either. This disconnect creates some of the best opportunities for value investors.

It’s all about recognizing the cycle we’re in, buying when sentiment is at its lowest, and waiting for the inevitable upswing.

The company looked attractive on a quantitative basis. Debt wasn’t a concern, and there were plenty of catalysts:

Market sentiment was at rock bottom, even though the company’s backlog was around $250 million - 3 to 4 times its market cap - and growing.

But of course, just having a large backlog doesn’t mean much if the company is operating barely on breakeven. It was also important to know that:

The aerospace industry, a major revenue driver for USAP, was hitting an inflection point.

The company faced demand issues during the COVID lockdowns, but there were clear signs of improvement. While product prices hadn’t yet caught up with inflation, the company was adjusting them month by month. This gave me confidence that as inflation slowed and demand grew, profitability was likely to return. Management has consistently emphasized this point during earnings calls as well.

Margins and earnings were on the rise, further strengthening my conviction. There was no justifiable reason for the stock to be this cheap. While it wasn’t worth $40, it also wasn’t worth just $10 per share, especially when you could liquidate the damn thing for probably twice that. Additionally, with insiders lacking majority control, a buyout offer became a realistic possibility.

So, I started buying shares. It was a classic 'buy low, sell high' scenario…

Timing could’ve been better, though

But, to my slight surprise, the stock kept sliding.

Down to $9, then $8.50, and then $8. With each drop, I kept digging to make sure I wasn’t missing something. But nothing convinced me that I was wrong.

When USAP was at its peak in 2018 the market acted like it would keep rising forever. At the bottom 4 years later, it seemed like the market thought that net loss would never again become net profit. But I knew otherwise. The signs were there.

The stock kept sliding, and I kept adding more.

I boosted my allocation to 10%. Then, 15%.

Then to 20% of my portfolio, as it dropped below $8 a piece.

It seemed like every time I thought it had hit the bottom, it went even lower. I decided to keep some cash aside, just in case the market got even crazier.

By the time it hit $6 per share, I had built it into a 30% position. I couldn’t justify such a low valuation with any logical reasoning. It was trading at ~30% of tangible book value. My calculations showed it was worth probably three times that. Both the steel and the aerospace industries were improving. Meanwhile, the market had completely given up on the company.

But, I knew I was right.

No borrowed conviction

This was before I even knew about Fintwit or the idea of a community of like-minded investors. My conviction had to come from just grinding through financial reports, doing my own research. I was simply following the logical steps that legendary investors had taken before.

It wasn’t until later that I found out this approach had a name - 'deep value'.

A lot has changed since I discovered Twitter. It was like finding a whole community of people who spoke the same language. People who saw value where others saw problems. It opened my eyes to a new world of opportunities, where complex situations with less competition could offer even better returns.

That’s also how I stumbled upon Orchard Funding Group.

Off-topic, but proves a relevant point

Value investing works because people are emotional creatures, prone to overreact in both directions.

The best opportunities, thus, often come from two sources: investors letting their emotions take over, or simply not doing the necessary work.

Although Orchard wasn’t a cyclical company, it exemplified a classic case where both dynamics were at play. After years of the stock’s relentless decline, frustrated long-time shareholders rushed for the exits. The price plummeted from 97p per share in 2015 to just around 37p at the start of 2024.

Over the next two months, the stock fell more than 50%, eventually reaching a bottom at just 20% of book value and a P/E ratio of 2. The tipping point came with the emergence of new regulations that would impact the company’s results. Most current investors hadn’t accurately assessed the extent of that impact, and the complexity of the situation deterred potential new buyers.

This created a setup ripe for outperformance - strikingly similar to the situation with Universal Stainless. A company left to die, forgotten.

It was, however, a lot more work…

Over the next two weeks, I immersed myself day and night, combing through every piece of information I could find. No detail was too minor; everything could be relevant. This wasn’t just about skimming reports; it was about understanding the business through facts, not rumors.

Unlike my experience with USAP, where I could build my conviction gradually as the stock fell, with Orchard there was this palpable sense of urgency in the air. Just as if that opportunity could vanish at any moment if the market caught on.

Hard work - reading every day until my eyes burned - was the only way to make sense of it all in time. I had to consciously choose the stock market over spending time with friends and family, acutely aware that I didn’t know how long I had before other investors discovered this opportunity.

There was no room for hesitation; I had to go all in from the start.

And, it paid off…

A month after my initial look at Orchard, the stock surged 70%. I got lucky, but more importantly, this was the result of doing diligent homework when others weren't willing to put in the effort. That kind of return-on-time-invested was incredibly good, especially with Orchard making up 15% of my portfolio.

…but it didn’t come easy.

The market was in full panic mode. Everyone and their mothers were selling, convinced that Orchard’s problems will ruin the company. I felt like I was standing alone, fighting against a tidal wave of pessimism. Even when I reached out to some of the sharpest minds I knew on Twitter, they weren’t biting. Sadly, no one was interested in joining in on the fun of sleepless nights and constant eye drop use.

And that is one way to approach investing.

Lessons learned

Orchard’s story wasn’t all that different from USAP’s. Both cases involved finding value that was actually quite obvious if you only looked closely enough. The market was too caught up in the noise to see that. The difference was in the approach:

USAP allowed me to ease in with a small position at first, then add more as I built conviction. The more promising the opportunity, the more work.

Orchard, on the other hand, demanded immediate action due to the sheer urgency of the situation. It was a solid company trading at just 20% of book value with a P/E of 2, after all. Opportunities like that don’t come around every day. The quantitative undervaluation was glaringly obvious. The real question was whether they will endure the recent issues. That was the qualitative part. And the latter is usually a lot more difficult than the former.

That experience taught me a key lesson:

In investing, the amount of work isn’t always linked to the size of the reward.

There are cases where value is hidden deep under the ground, which can take a lot more effort to uncover. When the fundamental signs are clear, as they were with Orchard, you often need to put in the time to confirm the facts - to assess the quality.

But not every opportunity requires complex modelling or hours of studying to reach a satisfactory level of conviction and a good potential return.

Sometimes, all you need to do is recognize when the market is visibly wrong and act.

That’s exactly why I pretty much always start with book value as a rough measure of value. My process is about keeping things simple. Spotting cases where value jumps right out at you. It’s just easier to scan for companies trading below book value, get a sense of their liquidation value, and figure out the chances of things getting better than it is to predict growth for the next 10 years or judge moat durability.

And the inherent inefficiencies in cyclicals make exploiting tangible undervaluations just too easy.

The company I’m about to discuss fits right into this approach. It’s trading at just around 28% of book value and 46% of NCAV. Profitable every year since 2012, but not today. And not because there is something wrong with it - it’s just cyclical.

Don’t get me wrong - there are plenty of people who do well focusing on growth stories and analyzing moats. That can work well too. But for me, the difference is that this way is just more straightforward and less time-consuming.

My returns have mostly come from sticking to this “easy” field. And if the simple way works so well, why complicate it?

End of part [1/2].

Hey, before you go…

If you’re not yet my subscriber, why not become one? I will provide you with regular writeups and updates on the cheapest deep value plays I come across. From mispriced cigar-butts, all the way to misunderstood special sits.

Transparency.

I’m all about being open with my picks and how they’re doing. You’ll get regular updates through “What’s in My Deep Value Portfolio?”—where I break down my current holdings, explain exactly why I think of my investments as also worth your while, and share how much I’ve put into each.

No noise.

I value your time as much as my own. You won’t see any “filler content”, no mile-long posts that take forever to read, but contribute nothing to your life. There’s plenty of that in social media already. My main goal as a writer is to provide you, as a reader, with the highest return on time and money invested.

You pay for value, I give you value.

I've got burned in the past by similar investments where time is not on your side. I.e. the longer this takes to play out the lower your return is. Do have a catalyst in mind?

What's the company :)